¡Feliz Navidad a Todos! / A Merry Christmas to One and All!

Jesucristo, el Gran Chamán: las pinturas de Norval Morrisseau, el mejor pintor canadiense del siglo XX / Jesus Christ, the Shaman: the paintings of Norval Morrisseau, Canada’s greatest painter of the 20th century

Sólo es que mis pinturas te recordan que eres Indio. En algún lugar, dentro, somos todos Indios. Entonces ahora cuando me hago amigo de tí, estoy intentando suscitar en tí el ser Indio – para que creerás en Todo como Sagrado.

(Norval Morrisseau / ᐅᓴᐘᐱᑯᐱᓀᓯ 1932-2007)

.

My paintings only remind you that you’re an Indian. Inside somewhere, we’re all Indians. So now, when I befriend you, I’m trying to get the best Indian, bring out the Indianness in you, to make you think Everything Is Sacred.

(Norval Morrisseau / ᐅᓴᐘᐱᑯᐱᓀᓯ 1932-2007)

Desde siempre estoy atraído por las pinturas religiosas, pero únicamente aquellas que tienen una naturaleza mística y supernatural – por ejemplo, la escultura de Santa Teresa por Bernini. Me da “vibraciones” – cuando cierro los ojos puedo sentirlas. Eso es gran Arte – y provoca en mí un hormigueo sexual. También occurre con San Sebastián. Pero es la figura del Jesucristo que es, para mí, la figura dominante. Así que por eso Cristo es El Gran Chamán – El Mejor. Así que por eso ciertas visiones religiosas son tan complejas y difícil explicar a la gente. Pues cuando miras mis pinturas estás mirando mis “visiones” – lo que sea que sean.

.

I have always been attracted to religious paintings, but only the ones that had that mystical or supernatural quality in them, especially Saint Teresa by Bernini. Just looking at Saint Teresa I get vibrations from it. I can close my eyes and feel them. That’s great art, and it brings on that tingling sexual feeling. Other saints, like Saint Sebastian, do that as well. But the Christ figure was always the one that was dominant for me.That’s why I say that Christ to me is still The Greatest Shaman, and that is why some religious visions are so complex – and so very hard to explain to people. So whenever you’re looking at my pictures, you are looking at my visions – whatever they may be.

Nosotros – los Nativos – creen en este dicho: Nuestro Dios es Nativo. Y es La Gran Deidad de los Cinco Planos. Somos “ni pro ni contra”, hablamos ni del Cristo ni de Dios. Decimos: Déjalo estar. Seguimos el Espíritu en su Paso Interior del Alma vía actitudes y atenciones. Recuerda: Estamos en una Escuela Grande…y El Maestro Interior nos enseña Experiencia – durante muchas Vidas.

.

We Natives believe in the following saying: Our God is Native. The Great Deity of the Five Planes is So. We are neither for nor against. We speak not of Christ nor of God. We say: Let them be. We follow the Spirit on its Inward Journey of Soul through attitudes and attentions. Remember: We are all in a Big School and the Inner Master teaches us Experience – over many Lifetimes!

Norval Morrisseau_Retrato del Artista como el Jesucristo_Portrait of the Artist as Jesus Christ_1966

. . . . .

መልካም ገና ! Melkam Gena: A Merry Ethiopian Christmas!

ᕿᓐᓄᐊᔪᐊᖅ ᐋᓯᕙᒃ / Kenojuak Ashevak: Inuit Artist Pioneer

ᕿᓐᓄᐊᔪᐊᖅ ᐋᓯᕙᒃ (1927-2013)

Kenojuak Ashevak was born in 1927 at the Inuit camp of Ikirasaq on Baffin Island in the North West Territories of Canada. She died exactly one year ago today – January 8th – and we are honouring her now, one year later, because ZP did not ‘post’ during the month of January 2013.

.

One of the first women to make drawings in Cape Dorset during the 1950s, Kenojuak used graphite, coloured pencils and felt-tip pens. With the assistance of Inuit art promoter James Houston, Kenojuak made the transition to soapstone-cut print-making. Her first such print dates from 1959 and is called Rabbit Eating Seaweed. It is based on a needle-work and appliqué design she had made on a sealskin bag. Kenojuak would draw freely, with confidence in line and form, then would have her drawings transferred/cut into the print stones by one of the stone-cutters at the new West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Workshop (“Senlavik”) which started up in 1959. After the stone-cutter had completed his incisions she would then apply one or two colours of inks to the printing surface. Sometimes the strong arms of Eegyvudluk Pootoogook would help apply the right paper-upon-stone pressure to complete the print. Kenojuak’s The Enchanted Owl, from 1960, is one of the most famous Canadian artworks internationally – instantly recognizable and emblematic of the 1960s and an “Idea” of The North.

.

Kenojuak was married three times and bore eleven children by her first husband, a hunter named Johnniebo Ashevak (1923-1972). At the time of her death from lung cancer in 2013, she was living in a wood-frame house in Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset), Nunavut. A cheerful personality, Kenojuak was always humble about her artistic success, and thankful for the “gift” of her talent.

The sealskin bag made by Kenojuak in 1958 and from which she drew the inspiration for her first print_Rabbit Eating Seaweed

. . . . .

“Sulijuk” – “It is true”: the drawings of Annie Pootoogook

Annie Pootoogook, born in 1969 in Cape Dorset, North West Territories – now Kinngait, Nunavut – began drawing at the age of 28, through the encouragement of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative. In 2006, she won Canada’s $50,000 Sobey Art Award, presented to artists age 39 or younger who have exhibited in Canada during the previous 18 months. In 2007 Pootoogook had drawings and lithographs at the 2007 Biennale de Montréal and also at the Basel Art Fair and Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany.

.

Pootoogook’s drawings are often in a style / with subject matter outside of traditional Inuit visual artistic style / subject matter. We are very far from The Enchanted Owl when we look at a Pootoogook drawing. “Modern” technology – video games, TV – are frankly present, even while boredom may also be evident in her human figures. The artist’s drawing technique of carefully outlining shapes in black then filling them in with solid colour is perhaps even more “traditional”, more “handmade” than most Inuit prints of the last two generations; and her subject matter is the opposite: no fantastic birds but her bra, her eyeglasses; no nostalgic Creation myth depicting Sedna, the goddess of the sea, rather a memory of Pootoogook herself smashing bottles against a wall.

.

An Artist may show many aspects of Life – both the real and the unreal, the ideal and the unvarnished truth. And anyway, such words refer to an interconnected reality that makes Existence “full up” with Being. That’s why Pootoogook’s drawings have validity – without belittling what had become a narrow genre in Inuit art i.e.the depiction of remembered “traditional ways” of daily life plus endless charming and fanciful Arctic animals. By the time Annie Pootoogook was born (1969) most Inuit in the Canadian Arctic had been forceably re-settled into permanent communities through a methodical programme of the federal government with the RCMP; they were living in pre-fabricated houses, and their former nomadic way of life – following the caribou herds and living in summer encampments then igloos – was gone in a mere two generations. While hunger ceased the Inuit were no longer self-sufficient yet neither were they integrated; the “violence” of such cultural upheaval is still being felt in 2014. Pootoogook’s drawings of domestic abuse and “boozing” tell this unpretty truth – and yet there is gentleness and humour in her work too, plus a straightforward and unsensational point of view about sometimes depressing circumstances.

.

After winning the Sobey prize Pootoogook moved from Baffin Island down to Ottawa. She went “outside” – as some Northerners say. By all accounts her life in The South has been up and down – yet she has not given up drawing. Annie Pootoogook is the daughter of artists – mother Napachie and father Eegyvudluk Pootoogook – and the granddaughter of Pitseolak Ashoona (1904-1983), one of the original generation of Inuit women illustrators/printmakers. Her uncle, Kananginak Pootoogook (1935-2010), was a sculptor and printmaker, and was instrumental in the creation of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative in the 1950s. So: Creativity is in Annie Pootoogook’s blood; we will be hearing from her again.

. . . . .

Annie Pootoogook outside the Rideau Centre in Ottawa making a drawing with coloured pencils_Summer of 2012

Black History Month: Favourite Albums: 1938 – 1983

.

Though Zócalo Poets is a poetry site – mainly – we are unable to resist the urge to post a Favourites list. Not a list of poems but of musical recordings; some of these are Songs, and, therefore, related to Poetry in its origins…What’s not to love about such an undertaking?!

Our Favourite Albums list for Black History Month 2014 is by no means definitive, for Music, like Poetry, is a limitless lifetime’s discovery. But here at least are some “snowed-in” Bests for February in Toronto…

. . .

Since there is no one album for Billie Holiday in the 1930s – generally there were only individual 78 rpm records with one song per side during that era – we have chosen her 1938 recording of Ray Noble’s “You’re So Desirable”. The 23-year-old Holiday sings it just right. And it was during this period – her early years – that she did her best singing. She was billed as the vocalist for various popular orchestras of the day – and was among the first singers to become more of a draw in performance than the band itself. From the time she was 18 and made her first recorded song – “My Mother’s Son-in-law”(1933), and clear through till the end of the decade, in songs such as “Travelin’ All Alone”(1937) and “On the Sentimental Side”(1938), Billie sang in her own new way – cheerful, spritely, yet also kind of lost: dreamy and sad – and often about a quarter-beat behind the band’s beat.

Paul Robeson recorded “Trees”, a song adaptation of a terrifically popular 1913 poem by Joyce Kilmer, in 1938 when he was 40 years old. Robeson’s voice was the deepest – yet full of nuanced feeling for all its bass ballast. A magnificent singer.

And take a few minutes to research his ambitious and complicated life. Robeson was a man of integrity; he really put his money where his mouth was – and paid the price.

Mongo Santamaría‘s 1959 album “Mongo”. Santamaria was a Cuban conga player, primarily handling the “quinto” drum which voices the lead in a percussion ensemble. Afro-Blue and Mazacote (“Sweet Hodgepodge”) are hypnotic tracks.

Nancy Wilson was 24 years old when she sang on this 1961 record, backed by George Shearing. To hear her sing “On Green Dolphin Street” is to hear young-smart-&-sophisticated. But in all that she sang from the 1960s – the pop standards, too – Wilson’s unique sound included a vocal clarity and precision unlike any other singer. The Song-Stylist to match!

Jackie Washington – born Juan Cándido Washington y Landrón in Puerto Rico but raised in Boston – was mainly known on the folk-music scene. He sang in English and in Spanish. This 1963 record includes “The Water is Wide” and “La Borinqueña”. A subtle and much under-rated singer.

The John Coltrane Quartet recorded A Love Supreme in just one session, on December 9th, 1964. It is a four-part instrumental suite – complex jazz, both introspective and forthright. Personnel included: Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones, and McCoy Tyner.

Wilson Pickett was one of the great R & B and Soul singers of the 1960s. And his earthy, rough and intense tone brings any lyric to life. The Exciting Wilson Pickett, from 1966, is 12 songs that play like jukebox Hits, many of them barely 2 and a half minutes long, and none more than 3 minutes. And how much time do you need anyway – when you’re the Wicked Pickett?

When Aretha Franklin recorded her first song, the brisk and bluesy “Maybe I’m a Fool” at the age of 18 in 1960, it was the beginning of a decade of superior-quality popular music from a young woman who quickly became one of the masterful song Interpreters of the 1960s. On Lady Soul, from 1967-68, Aretha sings two songs that show off her voice in different moods – and she gets ‘em both exactly Right-ON. The telling-it-like-it-is“Chain of Fools” and Carole King’s “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” (Aretha’s version of this is the one.) The Lady Soul album included among the background vocalists Aretha’s sisters Carolyn and Emma, and Whitney Houston’s mother, Cissy.

Miles Davis was making a transition from acoustic jazz to electric sounds when he recorded Filles de Kilamanjaro in 1968. Personnel included: Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock / Chick Corea, Ron Carter / Dave Holland, and Tony Williams. We far prefer this quirky album to the chilly perfection of Kind of Blue.

1969′s Outta Season! is all classic Blues from Ike and Tina Turner, with the addition of the old Spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”. We agree with Nat Freedland’s appraisal of Tina Turner’s voice and presence from this period: “Tina is such a fine singer and such a superlative performer that any reaction less than adulation seems pointless.” (Billboard magazine, October 1971).

Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway: In 1971-72 these two intensely-personal singers teamed up for an album that included soul, pop, and a powerful rendition of a 19th-century hymn, “Come, Ye Disconsolate”.

Al Green‘s 1972 album, I’m Still in Love with You: 35 minutes of exquisite Love Music. This was the Billboard chart #1 R.& B. album in December 1972, and Green’s pleading, confessional tone with a lyric makes you know why. Soul, Gospel, Pop, even a Country ‘feeling’ – all together as they rarely have been. “Love and Happiness”, “I’m Still in Love with You”, and “Look What You Done for Me” are standouts.

It’s hard to top Al Green’s album mentioned above – but Hedzoleh Soundz, an early 1970s combo. group from Ghana – with West African traditional and pop/rock musicians weaving into an Afro-Jazz sound – plus South African Hugh Masekela‘s trumpet sewing it all up – somehow DOES!

Bob Marley and The Wailers and the “I-Threes”, recorded live at The Lyceum in London, England, 1975. What can we say? The standard setter for great first-generation Reggae.

Esther Phillips has one of the best voices in recorded popular music – it may be too good, in fact. Her voice’s number 1 quality is Real-ness, and your ass’s been song’d by the time the needle leaves the groove. She was versatile, too – blues, jazz, country, pop – you name it, her voice held it all. Her 1972 version of Gil Scott-Heron’s “Home is Where the Hatred Is” is the definitive version of that disturbing drug-addiction cri-de-coeur (Phillips died at the age of 48, in 1984, after three decades of chronic hard-drug use.) If you can find a copy, listen to “All the Way Down” from the album pictured here, 1976′s Capricorn Princess.

Evelyn “Champagne” King‘s debut album, Smooth Talk, was released in 1977. The 18 year old had been cleaning offices and producer T. Life overheard her singing. He coached the teenager and in no time she delivered perhaps the single best Disco song ever – “Shame”. 6 minutes and 37 seconds long, it was a group effort, of course; there were real horns, plus guitar, bass, a drummer, keyboards, clavinet, organ, and a half a dozen judiciously-placed background vocalists. But King was a singer who could sing – her voice has a rawness and delicacy all at once – in other words, real character. It’s instructive to listen to a song like “Shame” nowadays and, if you’re old enough, you’ll remember when such mid-tempo dance songs were commonplace and that the bass beat was rarely punchy or mixed too big and too far forward. (Beware Remixes – such “pumped up” re-releases of quote-unquote Retro or Old-School dance numbers from a generation-or-more ago rob the songs of their integrity.) While many people made fun of Disco – even when it was “the trend” (approx.1976 – 1981) – it’s also true that too much of 21st-century Dance music (“Club” music) is pretty generic, features unmemorable voices, and requires a Video to make you believe you really Dig It. Are we showing our age here? Well, alright then.

Linda Clifford was given the full treatment for her 1979 Disco double-album, Let Me Be Your Woman: a cover portrait by Francesco Scavullo and an all-Woman centrefold (but classy!) when you flipped the jacket open. Clifford turns Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” into the funky disco anthem it should always have been, complete with “talking drums”. And “Don’t Give It Up” is 9 minutes of common-sense Rap – in its 1960s’ meaning: “keeping it real” and “having your say”. Clifford’s opening line: “Alright, Girls, come on now. We gonna have to git together and figure out what we gonna do with all these Men!”

“Balafon” and “Maracatu Atômico” from 1979 are examples of sweet-voiced Gilberto Gil‘s playful melding of Afro-Brazilian themes and rhythms with pop music – something so typically Brazilian. Brazil has the most variety musically of all countries on the planet; its musical inventiveness and hybrid vigour are unparalleled.

Jorge Ben, like his countryman Gilberto Gil, is restlessly creative on this 1981 album of Brazilian pop…

The Brothers Johnson‘s Blast! from 1982 contained the final great Disco track – “Stomp”. Yeah, it’s funky too, but make no mistake, this is Disco at its best, and a sexy, muscular last hurrah just as pop-music trends were veering off toward the self-conscious weirdness of New Wave.

The Pointer Sisters (Anita, June and Ruth) were a seasoned trio all in their thirties (fourth sister Bonnie struck out on her own in the late 1970s) by the time their 1983 album Break Out was released. Their strikingly-low alto voices combined with a synthesizer-dense instrumental made the song “Automatic” one of the quintessential 1980s tracks. The “12-inch” extended version of the song is an “Electro-Dance” classic of that decade. But it’s the Sisters’ rich, full vocals that really make the song.

. . . . .

Johnny Hartman: the great yet little known song stylist

Johnny Hartman (born John Maurice Hartman), 1923-1983, was from Louisiana but grew up in Chicago. Imagine the best qualities of Frank Sinatra’s voice from the 1940s and 1950s – tender and thoughtful, or manly with confidence – and you’ll have an idea of Hartman’s voice. Now: lower that voice to a baritone-bass – and you’ve got Hartman. Like Sinatra, he had a homely face and a great voice – but Hartman’s interpretive skills with a ballad were more sensitive – were finer – than Sinatra’s.

.

Contemporary singer Gregory Generet has written of Hartman: “ [He] was a master of emotional expression, putting everything he had into every word he sang. His rich, masculine baritone voice never wavered in its sincerity. The only vocalist ever to record with John Coltrane, he was mostly known only to true jazz lovers during his glorious career.” Generet’s correct when he writes “glorious”; he’s also correct when he writes “mostly known only to true jazz lovers.” Hartman’s performances on record are “glorious” and he was always too little known by the general public, and is by now all but eclipsed in the Internet-era that is the 21st century, where History is 10 years ago.

.

Listen to this 1955 recording of Johnny Hartman singing Cole Porter’s witty “Down in the Depths (on the 90th floor)”:

. . . . .

Wilson Pickett: Engine Number 9

Wilson Pickett (1941-2006) was born in Alabama into a family of many kids, and a father who was working up in Detroit, Michigan. In an interview in later years Pickett described his mother during his childhood: “She was the baddest woman – in my book. I get scared of her even now. She used to hit me with anything, skillets, stove wood… One time I ran away and cried for a week. Stayed in the woods, me and my little dog.” When he was fourteen he headed up to Detroit and lived with his father. It was then that he seriously began to sing in church ensembles that toured around; one of them, The Violinaires, helped him to really hone his singing skills. Gospel singers were beginning to “cross over” into the secular music market and this transition led the way to what would come to be known as Soul music. The Falcons, with Eddie Floyd, were at the forefront of this evolution, and Pickett joined the group at the age of 18 in 1959. His first songwriting began, with “I Found a Love”. “If You Need Me” and “It’s Too Late” would follow – but the latter two he recorded solo – commencing a career under his own name. James Brown is undisputably Soul’s Number 1 Man – but if you listen to Pickett and Brown, Pickett’s voice is undeniably more interesting – complex, capable of making almost bird-like shrieks, passionate and hoarse from crying? shouting? at Love gone wrong – or Love going oh so good…James Brown had the crazy looks and stage personality – but Pickett’s voice is richer, and takes more chances – making the weirdest deep-from-within sounds.

.

Listen to Wilson Pickett in this 1970 recording of Leon Gamble and Kenny Huff’s “Engine Number 9”. The instrumental sound is a hybrid of Blues and Rock, and Pickett’s voice is all Soul:

. . . . .

Hale Woodruff’s “Afro Emblems” and Ashanti Gold Weights

Hale Aspacio Woodruff (Cairo, Illinois, USA, 1900-1980) first grew interested in African art in the 1920s, when an art dealer gave him a German book on the subject. He couldn’t read the text but appreciated studying the pictures; on a trip to Europe some years later he bought African sculpture for his own personal inspiration. For “Afro Emblems”, Woodruff divided his canvas into rough rectangles, filling each shape with an emblem inspired by Ashanti or Akan gold weights. [ See paragraph below. ] Woodruff’s bold black outlines and dashes of colour stand out from the blue background, creating an abstract African-influenced pattern.

Ashanti or Akan Gold Weights

.

Natural gold resources in the dense forests of southern Ghana brought wealth and influence to the Ashanti (Asante) people. Wealth increased by transporting gold to North Africa via trade routes across the Sahara Desert. In the 15th and 16th centuries this gold attracted other traders, from the great Songhay Empire (in today’s Republic of Mali), from the Hausa cities of northern Nigeria and from Europe. European interest in the region, initially in gold and then in enslaved Africans, brought about great changes, not least the creation of the British Gold Coast Colony in the 19th century. (In 1959, this “Colony” de-Colonized, becoming the modern West-African nation of Ghana.)

.

Asante State had grown out of a group of smaller states to become a centralized hierarchical kingdom. By the early 1700s the Asante State’s increased power meant it was able to displace the former dominant state, Denkyira, which had, through conquest, controlled major trade routes to the Atlantic coast as well as some of the richest gold mines. Once the Asante became dominant in this region, both gold and slaves passed through its state capital, Kumasi.

Gold was central to Asante art and belief. Gold entered the Asante court via tribute or war and was fashioned into jewellery and ceremonial objects there by artisans from conquered territories. The court’s power was further demonstrated through its regulation of the regional gold trade. Everyone involved in trade and commerce owned, or had access to, a set of weights and scales. The weights, produced in brass, bronze or copper (usually by the ‘lost wax’ process), corresponded to a standardized weight system derived from North African / Islamic, Dutch and Portuguese precedents. Since each weight had a known measurement, merchants too employed them for secure, fair-trade arrangements with one another. Other gold-trade equipment included shovels for scooping up gold dust, spoons for lifting gold dust from the shovel and putting it on the scales and boxes for storing gold dust.

. . .

Hair’s to You: Baldheads, Dreads; Wigs & Things

. . .

Okhai Ojeikere (born Johnson Donatus Aihumekeokhai Ojeikere) died just over a week ago, on February 2nd, 2014, at the age of 83. Born in 1930 in the Nigerian village of Ovbiomu-Emai, he later mainly worked and lived in Ketu, Nigeria. At the age of 20 he decided to pursue photography; he began with a humble Brownie D camera without flash, and a friend taught him the technical fundamentals of the art. He worked as a darkroom assistant from 1954 till about 1960 for the Ministry of Information in Ibadan. In 1961 he became a studio photographer for Television House Ibadan, and from 1963 to 1975 he was with West Africa Publicity in Lagos. In 1968, under the auspices of the Nigerian Arts Council, he embarked upon an ambitious project of photo-documenting the many varieties of Nigerian hairstyles. He printed close to a thousand such pictures. A selection of Okhai Ojeikere’s prints was featured in the Arsenale at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. To honour Ojeikere’s life we present a century of Black hairstyles, with Ojeikere’s own photographs being Images 13 through 16.

.

.

Amor y un alma vieja: “Yendo a la deriva” por Jimi Hendrix

“Yendo a la deriva” (1970)

.

Yendo a la deriva

En un mar de lágrimas olvidadas

En un bote salvavidas

Navegando para

Tu amor: mi hogar.

Ah ah ah…

.

Yendo a la deriva

En un mar de antiguas angustias

En un bote salvavidas

Tirando para

Tu amor,

Tirando para

mi hogar.

Ah ah ah oooo ah…

. . .

Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970)

“Drifting” (1970)

.

Drifting

On a sea of forgotten teardrops

On a lifeboat

Sailing for

Your love

– Sailing home.

Ah ah ah…

.

Drifting

On a sea of old heartbreaks

On a lifeboat

Sailing for

Your love

– Sailing home.

Ah ah ah oooo ah…

. . .

. . . . .

Amor o Libertad: una canción “Soul” de los años 70: “Libre” por Deniece Williams

Deniece Williams (nacido en 1950)

“Libre” (1976)

.

Susurrando en su oído,

mi pocón mágica de Amor;

diciéndole que soy sincera

– y que no hay nada que es demasiado bueno para nosotros

.

Pero – quiero ser libre – libre – libre…

Y tengo que ser yo, sí, yo, sí – yo.

.

Manos coqueteandos en su cabeza

dan misterio a nuestras noches;

hay alegría todo el tiempo – ah, ¡como me complace ese hombre!

.

Pero – quiero ser libre – libre – libre…

Y tengo que ser yo, sí, yo, sí – yo.

.

Sintiéndote cerca de mí

hace sonreír todos mis sentidos;

no desperdiciemos nuestro arrobamiento

porque me quedo aquí solo un ratito

.

Y quiero ser libre – libre – libre…

Y tengo que ser yo, sí, yo, ah sí – yo.

. . .

Deniece Williams (born 1950)

“Free” (1976)

.

Whispering in his ear

My magic potion for love

Telling him I’m sincere

And that there’s nothing too good for us

.

But I want to be free, free, free

And I’ve just got to be me yeah, me, me

.

Teasing hands on his mind

Give our nights such mystery

Happiness all the time

Oh and how that man pleases me

.

But I want to be free, free, free

And I’ve just got to be me, me, me

.

Feeling you close to me

Makes all my senses smile

Let’s not waste ecstasy

‘Cause I’ll only be here for a while

.

And I’ve got to be free, free, free-eee, ohh-ohh

And I just wanna be me, yeah – me.

. . .

.

. . . . .

Lois Mailou Jones: Pioneer and Mentor

.

Boston-born Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998) was a painter, art teacher and mentor, who taught at Howard University in Washington, D.C., for almost half a century. Jones was of that generation of trail-blazers in Black-American art; and among Black women she was one of the first to establish an artistic reputation beyond the USA. Jim-Crow “policies” still being entrenched, her early entries into art exhibitions were sometimes rejected when organizers discovered that the paintings were by a Black person; Jones from time to time had Céline Marie Tabary – a Parisian fellow-artist who came to teach at Howard for a decade or so – deliver her paintings (especially after an award was taken away from her upon the “revelation” of her race.)

In 1934 Jones had attended a summer session at Columbia University, and began to study African masks and to incorporate depictions of them into her oil studies. “Les Fétiches” (1938), her painting of several African masks grouped together, Jones painted while visiting Paris where she also absorbed some of the “active” artistic philosophy of the French-Caribbean-African Négritude movement. (Léon Damas, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Aimé Césaire spearheaded that mainly literary Black-Francophone movement.)

After a letter correspondence lasting many years, Jones and Haitian artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel married in 1953. They took trips to Haiti and also to African nations during the 1960s and 1970s. Haitian and pan-African themes became central to Jones’ work.

Lois Mailou Jones’ most important achievement may be that she was an exacting and supportive mentor to younger generations of Black artists, among them Martha Jackson-Jarvis and David C. Driskell.

.

. . . . .

Danny Simmons: Abstract Expressionism via “Oil on Smartphone”

.

Daniel “Danny” Simmons, Jr., is a painter from Queens, New York City. Self-taught, he used to watch his mother, an amateur painter, while she worked. In the early 1990s he began to concentrate seriously on painting, incorporating influences from Catalan painter Joan Miró, and developing a style he calls Neo-African Abstract Expressionism. His artwork is in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, The Shomburg Center for Black Culture, and The Smithsonian. In 1995, with his brothers Joseph and Russell, he founded Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation, out of which grew Rush Arts Gallery in Manhattan and Corridor Gallery in Brooklyn. Though he has long painted in oils, recently Simmons has started to make “Digital Prints” – Smartphone Art. Using a Samsung Galaxy Note II phone and the accompanying stylus he has learned a new way to draw and paint using the device’s embedded app. Rather than printing multiples of these phone-sketches or phone-paintings he prints just one – making it an original artwork with value beyond a print. Simmons uses a professional digital printing house whose staff vectorize the image files so that the resolution holds together and then they print the images on high-quality paper. Asked what he thinks about when he’s painting – and “painting”– Danny Simmons has said: “I’m really trying to get at how people are connected to each other and invoke the feeling that these paintings are taking you to a place where a lot of people can be transported to at the same time, and find a common ground there. Society is so polarizing – between rich and poor, races and religions – but one of the things that can bring people together is art.” (Quotation from WhiteHot magazine interview with Paul Laster, December 2013)

.

. . . . .

Willie Cole: Neo-African sculpture with American plenty

For the decade of the 1990s, Willie Cole (born 1955) was inspired principally by the archaic cast-iron steam iron. The Newark, New Jersey-born sculptor and conceptual artist created faux-anthropological research into The People of Iron a.k.a. The Cult of The Domestic. By the end of the decade he had chronicled their journey from slavery to freedom through sculpture, printmaking – and branding (with iron, that is). The elliptical association with the fact of American slavery cannot be missed by any viewer with historical intelligence. Cole’s shoe sculptures, and those with hair dryers, bicycle parts, kitchen chairs and so forth, are visually strong and metaphorically rich – and only an African-American sculptor could use materials in this way to create something fresh and “American” yet linked to the beauty of African “traditional” art.

. . . . .

“Many People – One Carnival”: J’Ouvert Morning…An’ de lime go be good !

Kaiso – Calypso – Soca: Pepper It T&T-Style !

McCartha Linda Sandy-Lewis, better known as Calypso Rose_The greatest of the female Calypsonians, and still going strong in her 70s…

.

Through great ex-tempo performers, singers, composers and arrangers, Calypso music has been evolving for more than a century. The Roaring Lion, Lord Invader, Lord Pretender, Lord Kitchener, Calypso Rose, Lord/Ras Shorty, David Rudder – the list could go on and on; so many have been innovators or have deepened the tradition. Political, social and sexual commentary, as well as a healthy joie-de-vivre for fête-ing, have all characterized Calypso. The music has branched out into Chutney Soca via Indian pioneers such as Drupatee Ramgoonai; has voyaged through temporary influences from Ragga and Dancehall; has even fallen prey to the ghastly Auto-Tune audio processor so rampant in popular music. Still, Calypso at its best – and it still can be at its best – can’t be beat. (Except maybe by Pan !)

.

Julian Whiterose’s “Iron Duke in the Land” – the first-ever Kaiso (Calypso) recording, from 1912:

.

Lord Executor’s “I don’t know how the young men living” (1937):

.

Frederick Wilmoth Hendricks a.k.a. Wilmoth Houdini (1895-1977)_1939 Calypsos recorded in NYC by the Trinidadian native

A recording of a 1946 Calypso concert in NYC featuring Lord Invader, Duke of Iron, and MacBeth the Great

The Mighty Sparrow’s “Jean and Dinah” (Yankees Gone) (1956):

.

Calypso Rose’s “Palet” (Popsicle) from the 1970s:

.

Lord Shorty’s “Endless Vibrations”(1974):

.

Black Stalin (Leroy Calliste, born 1941, San Fernando, Trinidad)

“Caribbean Unity” (1979)

.

You try with a federation

De whole ting get in confusion

Caricom and then Carifta

But some how ah smellin disaster

Mister West Indian politician

I mean yuh went to big institution

And how come you cyah unite 7 million?

When ah West Indian unity I know is very easy

If you only rap to yuh people and tell dem like me – dem is:

.

One race (de Caribbean man)

From de same place (de Caribbean man)

Dat make de same trip (de Caribbean man)

On de same ship (de Caribbean man)

So we must push one common intention

Is for a better life in de region

For we woman, and we children

Dat must be de ambition of de Caribbean man

De Caribbean man, de Caribbean man…

.

You say dat de federation

Was imported quite from England

And you goin and form ah Carifta

With ah true West Indian flavour

But when Carifta started runnin

Morning, noon and night all ah hearin

Is just money-speech dem prime minister givin

Well I say no set ah money could form ah unity

First of all your people need their identity, like:

.

One race (de Caribbean man)

From de same place (de Caribbean man)

Dat make de same trip (de Caribbean man)

On de same ship (de Caribbean man)

So we must push one common intention

Is for a better life in de region

For we woman, and we children

Dat must be de ambition of de Caribbean man

De Caribbean man, de Caribbean man…

.

Caricom is wastin time

De whole Caribbean gone blind

If we doh know from where we comin

Then we cyah plan where we goin

Dats why some want to be communist

But then some want to be socialist

And one set ah religion to add to de foolishness!

Look, ah man who doh know his history

He have brought no unity

How could ah man who doh know his roots form his own ideology? – like:

.

One race (de Caribbean man)

From de same place (de Caribbean man)

Dat make de same trip (de Caribbean man)

On de same ship (de Caribbean man)

So we must push one common intention

Is for a better life in de region

For we woman, and we children.

Dat must be de ambition of de Caribbean man

De Caribbean man, de Caribbean man…

.

De Federation done dead and Carifta goin tuh bed

But de cult of de Rastafarian spreadin through de Caribbean

It have Rastas now in Grenada, it have Rastas now in St. Lucia,

But tuh run Carifta, yes you gettin pressure

If the Rastafari movement spreadin and Carifta dyin slow

Then there’s somethin that Rasta done that dem politician doh know – that we:

.

One race (de Caribbean man)

From de same place (de Caribbean man)

Dat make de same trip (de Caribbean man)

On de same ship (de Caribbean man)

So we must push one common intention

Is for a better life in de region

For we woman, and we children

Dat must be de ambition of de Caribbean man

De Caribbean man, de Caribbean man!

.

Caricom:

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) is an organization of more than a dozen nations and dependencies, established during the 1970s. Its main purposes have been to promote economic integration and cooperation among its members, to ensure that the benefits of integration are equitably shared, and to coordinate foreign policy.

The Caribbean Free Trade Association was formed in the 1960s among English-speaking Caribbean nations to make economic links more streamlined. Diversifying and liberalizing trade plus ensuring fair competition have all been CARIFTA goals.

.

Black Stalin’s “Caribbean Unity” (1979):

.

Crazy’s “Young Man”(1980):

.

Explainer’s “Lorraine”(1981):

.

The Mighty Gabby (an honorary Trini!): “Boots”(1983):

.

Lord Nelson’s “Meh Lover” (1983):

.

The Mighty Shadow’s “Jitters” (1985):

.

David Rudder and Charlie’s Roots: “The Hammer”(1986):

. . . . .

Kerbel, Terada, Nauman: three Wordy conceptual artists – But Wait, There’s More!

Janice Kerbel_one page of A letter by Rodolphe Boulanger de Huchette to Emma Bovary written by Gustave Flaubert in my hand

Currently, at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Canada, there are works from the permanent collection on view by three conceptual artists who use words – just a phrase, or a crammed page – as the locus of their art. The artists are: Janice Kerbel (born 1969, Canada, now living in London, England); Ron Terada (also 1969, Canada); and Bruce Nauman (born 1941, USA).

Kerbel’s 5-poster series Remarkable, from 2007, presents the viewer with silkscreened prints on what is known as campaign poster paper – something used for 19th-century traveling circus billboard “announcements” or for election hoardings. Using bold black letters on white, Kerbel describes The Regurgitating Lady and The Human Firefly, as if inviting us in to a carnival side-show. Yet her characters are imaginary and so we become completely involved in the artist’s sometimes archaic use of language and her strong typographical arrangements.

Janice Kerbel_silkscreen print on campaign poster paper_The Temperamental Barometric Contortionist_2007

Vancouver-based Ron Terada has been very precisely focused in his art on phrases, sentences, written presentation. Twenty years ago he did a series of “ad paintings” that were a branching out of monochromatic minimalism in visual art. He worked in other media for several years then returned in 2010 with the large-scale white-on-black chapter pages of “Jack” (from a biography of painter Jack Goldstein, Jack Goldstein and the CalArts Mafia). Each chapter page is a painting – not a print. To the individual pages of a book, Terada brings the discipline of a serious painter.

Ron Terada’s neon text sculpture, It Is What It Is, It Was What It Was, reflects on present-day use of language, offering a general critique of complacency in society. Severe High makes reference to threat definitions for Homeland Security in the USA.

Bruce Nauman is a multimedia artist who has been heavy on “concept” and “performance”. The online, user-driven encyclopedia Wikipedia describes Nauman’s “practice” as being “characterized by an interest in language, often manifesting itself in a playful, mischievous manner.” And: [Nauman is] fascinated by the nature of communication and language’s inherent problems, as well as the role of the artist as a supposed communicator and manipulator of visual symbols.”

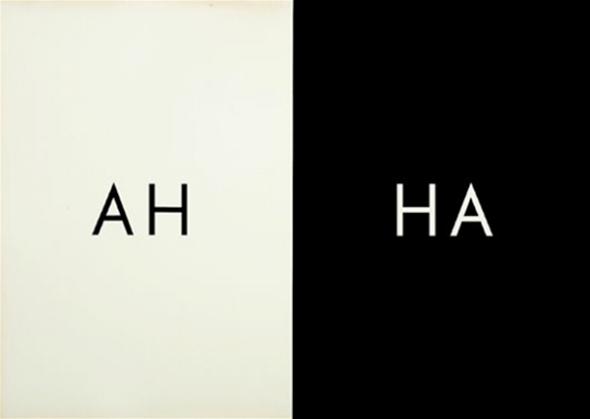

Among the A.G.O.’s pieces are two lithographs, Ah Ha (1975) and Pay Attention (1973):

The reproduction of Pay Attention shown here (copied many times around the internet) is marred by the lack of print clarity in the word attention, which affects the viewer’s – reader’s ! – ability to quickly “get it”, that is, the power of the statement itself: Pay Attention, Motherfuckers! Interestingly, the print of Pay Attention that belongs to the A.G.O. is much clearer, so that all four words hit the mark. Which is important, especially since the statement is presented to us as a mirror image i.e. backwards.

Some of Nauman’s works now seem dated or stilted, but others have a fresh power in 2014 that comes out of our being awash now in “text” – as all words seem to be called these days – and “text” often without “context”. People’s ubiquitous use of :-) and, most especially, ;-), is indicative of the fact that words and phrases themselves are no longer adequate. What’s the tone – what’s the tone? It’s there you’ll find the meaning. The most effective of all the Nauman works at the A.G.O. is a 1985 videotape installation, Good Boy Bad Boy. There are two older-model TV sets side by side, and each shows its own videocassette of a man – mid-40s black guy, and a woman – mid-40s, white – each of whom speaks a set group of short sentences which are statements, and then does it all over again, but altering the vocal tone. To hear each of them “perform” these statements twice, changing his/her tone, is a simple and clear demonstration of the complexity and muddiness of Language. The man says: I was a bad girl. You were a bad girl. We were baaad girls. We were baaaaad! And he’s enjoying remembering being a slut. The woman says the same things and she is a scolding puritan; she may be speaking of a pet dog who pooped on the Persian carpet, or of two 12 year olds caught smoking cigarettes. Same phrases – entirely different meanings. A good contemporary example of this is two words: Hello and Whatever. Both have pleasant or neutral uses in conversation but both also can be altered via tonal change, pitch, even syllable stress, to communicate irate impatience or deliberate rudeness (Hello); and casual defiance or a kind of hybrid attitude of blasé and crass (Whatever).

Nauman is quoted at the A.G.O. exhibit: “When language begins to break down a little bit it becomes exciting and communicates in nearly the simplest way that it can function. You are forced to be aware of the sounds and the poetic parts of words.”

Some of Honest Ed’s iconic handpainted signs on display in 2012_Wayne Reuben has been, for decades, that man with the calligraphy brush and the poster paints.

Honest Ed’s signpainter, Wayne Reuben, at work in July 2013_photograph by Darren Calabrese, National Post

To whom shall we give the last Word? Why, Wayne Reuben – of course!

Wayne Reuben is the man behind the sometimes wacky ads, proclamations, commands and price cards at Honest Ed’s discount store, the building structure of which is a vivid Toronto landmark, what with the thousands of marquee bulbs that light up its red and yellow exterior. It’s Reuben’s handiwork when, out on the sidewalk, you read: Come In And Get Lost! And it’s Reuben’s blue and red paint letters that tell you, once you’re inside: Don’t Just Stand There – Buy Something!

Two weeks ago, hundreds of Torontonians lined up around the block to get the chance to pore over Mr. Reuben’s thousand-plus handpainted signs that Ed’s never trashed over the decades. The lucky buyer might’ve come away with Fancy Panties or Men’s Mesh Tops, a sign in the shape of a Hallowe’en pumpkin that reads WIGS $6.99, lovingly handpainted price boards for tinned sardines, coconut milk, hair grease or pomades – even Justin Bieber-photosilkscreened pyjamas. Along with Doug Kerr, the left-handed Reuben writes/paints in something like a serif font (and sans serif), to spell out Ed’s commercial message; and the tempera paint palette is strong and basic: blue, red, yellow, black.

So why would people line up to buy ephemeral signboards for 5 to 40 dollars? Is it nostalgia for the handmade? Or the curvilinear ease of Reuben’s brushstroke? No. It’s because Honest Ed Is For The Birds: Cheap Cheap Cheap!

;-)

Itee Pootoogook (1951-2014): A Tribute in Poems

Itee Pootoogook, an Inuk and artist from Kimmirut, Baffin Island, was born in 1951 to Ishuhungitok and Paulassie Pootoogook. His drawings are characterized by an uncluttered gaze that sees what is directly before it, and an ability to find the profound in the simple. He died earlier this month of cancer; he was 63 years old.

Some artists are rooted in a place; this was Itee Pootoogook, very much so, and his drawings depict life in Nunavut. But great art travels, becomes universal. And so we have gathered poems from Germany, Russia, India and the USA, to accompany a selection of Itee’s drawings…

. . .

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962)

On a Journey

.

Don’t be downcast, soon the night will come,

When we can see the cool moon laughing in secret

Over the faint countryside,

And we rest, hand in hand.

.

Don’t be downcast, the time will soon come

When we can have rest. Our small crosses will stand

On the bright edge of the road together,

And rain falls, and snow falls,

And the winds come and go.

. . .

Hermann Hesse

How Heavy the Days

.

How heavy the days are,

There’s not a fire that can warm me,

Not a sun to laugh with me,

Everything bare,

Everything cold and merciless,

And even the beloved, clear

Stars look desolately down

– Since I learned in my heart that

Love can die.

.

Translations from the German: James Wright

. . .

Mohan Rana (born 1964, Delhi, India)

After Midnight

.

I saw the stars far off,

as far as I was from them,

in this moment I saw them,

in a moment of the twinkling past.

In the boundless depths of darkness,

these hours hunt the morning through the night.

.

And I can’t make up my mind:

am I living this life for the first time?

Or repeating it, forgetting as I live,

that first breath – every time?

.

Does the fish too drink water?

Does the sun feel the heat?

Does light see the dark?

Does the rain also get wet?

Do dreams ask questions about sleep – as I do?

.

I walked a long, long way…

and when I saw, I saw the stars – close by.

Today it rained all day long

and words washed away from your face.

.

Translation from Hindi: Lucy Rosenstein and Bernard O’Donoghue

. . .

Itee Pootoogook_The ground is wet for it’s been raining during the night…It is early fall and it’s early morning_pencil crayon on paper_2010

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

from: Poems for Blok (1916)

.

Your name is a—bird in my hand,

a piece of ice on my tongue.

The lips’ quick opening.

Your name—four letters.

A ball caught in flight,

a silver bell in my mouth.

A stone thrown into a silent lake

is—the sound of your name.

The light click of hooves at night

—your name.

Your name at my temple

—sharp click of a cocked gun.

Your name—impossible—

kiss on my eyes,

the chill of closed eyelids.

Your name—a kiss of snow.

Blue gulp of icy spring water.

With your name—sleep deepens.

.

Translation from the Russian original: Ilya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine

. . .

Angelyn Hays (Texas/Florida, USA)

One of the Cardinal Seasons

After the hardest snow of the year

the birches huddle in rows.

Ice breaks their wooden bones,

and hangs them by the thumbs

in a March sun too weak to heal them.

Birds call to each other

from the tangle of bare arms.

A red-dark Cardinal feasts in my backyard,

singing to warm his lungs. He enters

just as I am ready to leave.

I had stopped the clock,

put away my mother’s china,

and wanted to sink to timeless black.

But the bird came for me,

signaling me to rise, recall his password.

The window is framed by trees, no longer trees,

sky, no longer sky, but now a watch

by which I measure my days.

Shouting the weight of his pleasure

from fevered beak, he rolls a black eye

and we click off the minute.

Then he swoops over my white garden,

drunk as Li Po, his floating path

a dance on an empty swingset of wind.

Michael Valentine (Maryland, USA)

A Meadow in March

.

Early Spring snowfall

dusts late Winter bloom

crystalline fractals piling gently

all around

to rest upon vibrant petal

leaf

stem

and ground.

The field now

a riot of pixelated colour

struggling to be seen under

blank canvas tarp of

Winter’s last throes.

Portrait of Nature’s perfect balance

Yin meeting Yang

flowing together

each becoming the other

flower melts snow into water flowing into flower.

Demonstration of Tao

in this limbo-time between the seasons

that is no longer Winter

and not yet Spring,

when the Universe gives lessons

to remind us that

there is no such thing as

“impossible”.

. . .

Mitchell Walters (Temecula, California, USA)

The Shack

.

I walked to the river and back.

Something told me I should.

I saw things I hadn’t seen before:

A dog. A deer. A stream.

.

I saw an old abandoned shack.

It was made entirely of wood.

I walked to the shack and opened the door.

And that was the start of my dream.

. . . . .

La Pasión de Jesús en imágenes / The Passion in pictures

Mary Magdalen at the foot of The Cross as Jesus suffered_an 1886 stained glass window from Saint Bledrws Church in Wales

Macha Chmakoff_At the foot of The Cross_Abstract painting based on John 19: verses 25- 27_The women gathered at the cross included Mary, mother of Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Giotto_La cattura di Cristo (Il bacio di Giuda)_The arrest of Christ (The kiss of Judas)_fresco in Padua, Italy_painted in 1306

La Agonía en el huerto de Getsemaní_The Agony in the Garden_Jesus at Gethsamane praying while His disciples sleep_a stained glass window from Ebreichsdorf chapel in Austria_1390s